- the dead zine.

- Posts

- Generational grief at the table

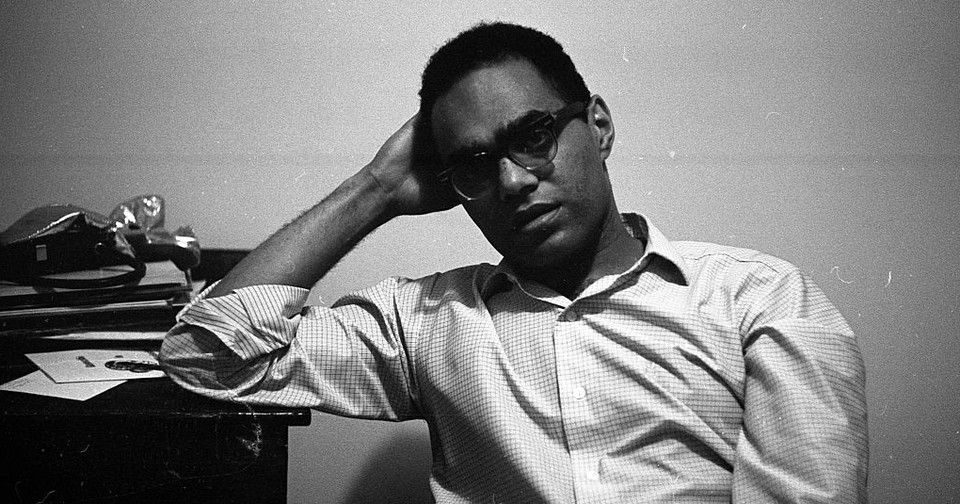

Generational grief at the table

Issue 007

There’s this story I tell often about my Dad with a slight smirk. It’s one about how as a Black little girl growing up in the suburbs of Atlanta, I became indoctrinated with all the Nigerian foods vis a vis my father, huddled in a small kitchen, smelling the fiery stews from a distance.

My Dad started offering Nigerian stew to me almost as soon as I could eat solid food. Thinking back through my childhood, there are endless memories of him intertwined with the food I ate. Because of this, it’s no surprise that my grief feels most bottomless when I’m thinking about food and how my Dad and I shared so many meals together.

In the last years of his life, I often acted as his caretaker, shuttling him to doctor’s appointments, taking him to urgent care if he had an emergent health crisis, picking him up from outpatient procedures, picking him up or dropping him off from the dialysis for his failed kidneys he had to attend three times per week when his eyesight prevented him from driving anymore.

But I also cooked for him in the evenings: big bowls filled with saffron rice, salad, hummus, blocks of feta sprinkled with smoked sea salt, chicken and fresh pita; brown stew chicken and curries so hot they reminded me of Nigerian food. I poured love into each plate I placed in front of him those evenings because I knew, even when he did not profess how weary he was from living, that he could use a reminder of the softness of being considered. That was my gift to him, that was how I practiced the devotion only reserved for my Dad and that is where I tuck my grief for when it is most convenient, less bothersome for an era of mourning.

Really this approach isn’t any better though. Because it means each time I saunter into the kitchen willing my appetite to arrive, I think of my Dad, wondering what I was cooking and wanting to taste some of whatever I was concocting. In the kitchen, when I’m alone with my thoughts and the noise from the world is a little more quiet, I can touch my grief in flashes, like touching the heat from a pot smoldering on the stove. Hot to the touch, terrifying and fleeting.

There’s this saying that has become popular online in recent months and years about how for some generations, it finally becomes safe to feel all that those before felt. That the role of some is to feel and to bask in all that has raged and hurt us. I think that grief is this way, too. I do believe that generational grief tarries and hangs in the balance with most of us. When we mourn, it spills out touching everything in its path, catalyzing what meaning-making shall be in the most immediate future.

For us Black immigrant kids, generational grief has a certain aroma. When it hits our tongues, we can taste the longing for a home that shrunk away from being good enough or safe enough. We taste all the endless sacrifices that are held over our psyche by our parents, aunties and uncles and other elders who desire to distract us into obedience and submission.

The flavor of generational grief is ever-shifting, never the same. Sometimes it doesn’t taste like sacrifice but instead of a void for any real pleasure, play or fun because survival has always felt more urgent, more important. The morsels of forgotten crumbs from a dish already served and eaten can fill us with regret—for what never was, for what will never be and all the possibilities that swirl in-between.

And yet, for those of us who are descendants of the enslaved in this country, our generational grief is rationed out in moments, siloed through markers in time that almost no one wants us to punctuate. We forge forward, each new generation, thinking that it’ll be different, be better. And in some respects, it is. Our grief is dimmed, more palatable, in the latent assumption that better or some sorta titled forward movement erases all the pain, all the injustice, abandonment, violence and neglect.

But it always comes roaring back, right there on the damn plate, nestled there in-between candied yams and mac and cheese. Our grief lies in a searing degree of unacknowledgement— as people who have always had to endure far too much to make a life and deem themselves among the living. The taste of our grief is sour, satiating yet unrelenting. Interesting yet not enough for replete fulfillment. We leave the table wanting and hungering for more, knowing there is nothing more to be gathered or given. We will simply have to exist in a wanton state of need. Always needing. Always grieving. Always wondering.

Consider this the next time you sit down to eat—how generations that came before you and subtly, those who are to come after—feast from the same metaphorical plate. A plate of unending complexities that reveal themselves with each flick of a fork or napkin that has found its home crumpled waiting for some day, some moment, to be unfurled.

Enjoying what you’re reading? Want to support this week? Consider becoming a paid subscriber for $7/month or $70/year!

Reply